The announcer said in the teaser said that Angie Harmon would learn about a relative who was bought and sold, and that her ancestor had something to do with a pivotal point in American history. Considering the dramatic delivery, at first I wondered if it might have something to do with the Civil War, but since there was no hint that Harmon was going to learn she had a black ancestor, and I really didn't think WDYTYA would spring that on everyone with no warning, I figured they used that phrasing just to throw us off.

Harmon is shown in the opening segment with her three daughters. She tells them that she is going to learn about their ancestors. We are told that she is an acclaimed actress ([cough, cough] two awards over a "career" [such as it is] of twenty years do not an "acclaimed actress" make). She went from being a model to appearing in movies and on television. Her best known series are Law & Order and Rizzoli & Isles (which at least has Sasha Alexander, who used to be on NCIS; and speaking of NCIS, no, Angie Harmon does not appear to be related to Mark Harmon). She is an ambassador for UNICEF, particularly focusing on campaigns against child trafficking.

Harmon lives in Charlotte, North Carolina with the aforementioned three daughters. At no time on the program is their father mentioned; apparently Harmon and her husband separated in 2014. Harmon herself is an only child, but her mother and father each have three siblings. She grew up knowing all her cousins, who were her age, so it was like having siblings of her own.

Harmon grew up in Dallas, Texas. She was with her mother until she was 11, and then "switched over" (her phrase, not mine) to be with her father. She knows her mother is 100% Greek, but doesn't know as much about her father. She is convinced he has Irish or Scottish ancestry but has less actual information about his family. His parents were Henry Harmon and Velma Daugherty. And that's about all she knows. She also talks about how she is a very strong person and very resilient, and how she would like to know where in her family that comes from.

Next we see Harmon walking with her daughters again. She says she hopes she finds some pictures of ancestors during her research and asks the girls if they think some pictures might look like her. Then she talks about how she loves family and is really interested in learning about her ancestry. Her father was a history teacher, and she loves history also. She wants to share the information she learns with her daughters, because it's their heritage too.

The "research" begins with a letter from Harmon's father. She is at home with her daughters and reads the letter to them; she says it came from "Poppoo" (that's the closest I can come to approximating how she pronounced it; apparently it's what they call their grandfather). He said he was sending pictures of people she had never known and how dedication to family was part of her genetics. (Gee, I didn't know that was a genetic trait.) However many photos he actually sent, we get to see only one, of Harmon's grandparents, Henry Jefferson Harmon and Estella McGoldrick Harmon, with five children. When Harmon prompts the girls what Henry and Estella's relationship is to them, one correctly answers great-grandparents. When Harmon says she's going to a genealogist for help to learn more about the family, however, we hear a small voice in the background say, "Or a genie?" I think that's a great idea — can you imagine how much easier your research would be if you had a genie to help you find documents?

Harmon begins the next stage of her learning experience by driving to the Charlotte Museum of History. On the way we hear that she had sent the information she had to genealogist Joseph Shumway (of Ancestry.com; I think it's at least his sixth appearance on the program?), who will be meeting her at the museum. Shumway says that he took the information and used vital records, land records, newspapers, and other information to go back on the Harmon line. (It's nice to see the show acknowledging more of the records used in research, even if it's only a quick passing mention.) Now the ubiquitous computer appears, a little later than usual recently but already logged into Ancestry.com, and Shumway says he has put together a family tree. Harmon sounds genuinely enthusiastic and sincere when she says, "Thank you!"

The initial shot of the tree, which shows Harmon and her parents, is not focused (living people, you know). Her father, however, is Larry Paul Harmon. His parents were Henry Harmon, Jr. (1914–1994) and Velma Evelyn Daugherty (1916–2012). Henry's parents were Henry Jefferson Harmon, Sr. (1882–1956) and Celia Estella McGoldrick (1878–1966). Harmon mouses over each, and we see more details: Henry Sr. was born June 20, 1882 in Missouri and died September 5, 1956 in Oklahoma; Estella was born December 11, 1878 in Missouri and died December 17, 1965 in Cushing, Payne County, Oklahoma. From there we go to the floating sky tree and travel back to Harmon's 5th-great-grandfather: Larry to Henry Jr. to Henry Sr. to James George Harmon to Thomas Jefferson Harmon (how patriotic!) to Peter Harmon to Michael Harmon.

At Michael we return to the computer screen shot. The icon shows that Michael was born in 1754 but has no death year. As Harmon mouses over it, we see that he was born in Germany. This flabbergasts Harmon, who had no inkling she had any German ancestry. After Shumway tells her to click on the box for more details, the computer goes to a different view, which includes an entry that says Michael Harmon arrived in 1772 to Philadelphia. (If you look quickly, you can also see that Michael's son Peter lived 1782–1853.) Harmon notes Michael was about 18 years old when he arrived in Phillie.

|

| index entry from Ancestry.com |

Harmon has never been to Philadelphia before. She goes to the Historical Society, where James Horn, Ph.D., of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation greets her. (On the WDYTYA episode with Reba McEntire, we were told he specializes in indentured servitude as a research subject.) Horn has a book with records for apprentices and servants in the city of Philadelphia. Michal Harman appears in the index; when Harmon goes to the referenced page, the entry at the top of the page shows that he arrived December 23, 1772 and was contracted for 5 years and 7 months to William Will of Philadelphia, who paid £23..5 (23 pounds and probably 5 shillings) for his passage from Rotterdam. (After previously noticing Harman versus Harmon, she doesn't seem to note that his name is spelled Michal on this page.) They discuss how people didn't have to pay their fares up front but could contract to pay at their destinations. Those passengers were then hoping that a merchant, ship's captain, or someone else would pay when they arrived. Horn explains they were auctioned off to the highest bidders. Indentured servitude was common in this period. The servant was bound by contract, had no say in the choice of bidder, and received no wages during the period of servitude. Horn adds that Michal would likely have known before he departed on the ship what he was getting himself into.

Harmon asks what happened to Michal next, and Horn says that she "might actually be able to learn a little bit more" by reading the second entry on the same page. That entry shows that William Will turned around and assigned Michal's contract to John Houts, a tanner, for the same period and same amount of money. This leads to a discussion about the type of work a tanner did — skinning carcasses and processing the leather, pretty hard work. Harmon looks a little uncomfortable but manages to carry on. (Maybe she's a vegetarian?) Horn also emphasizes that indentured servants were essentially a commodity. (But what did William Will get out of it? There's no profit in the way he appears to have done the two transactions. Maybe Houts was a friend and he was doing a favor?)

Harmon wants to know why Michal would have left his home and asks what Germany was like at the time. The big problem for young men such as Michal was that little land was available. Horn says that land was the ultimate test of worth. This situation convinced many people, who often became indentured servants, to leave just for the opportunity to have land of their own.

Doing some quick math in her head, Harmon figures out that Michal should have been finished with his contract in 1778. Horn agrees but points out that the American Revolution against the British was going on by that time. He asks Harmon what was going on in Philadelphia and where Michal was. She sounds concerned and asks him, "Do we know?" He responds, "That's what we've got to find out!"

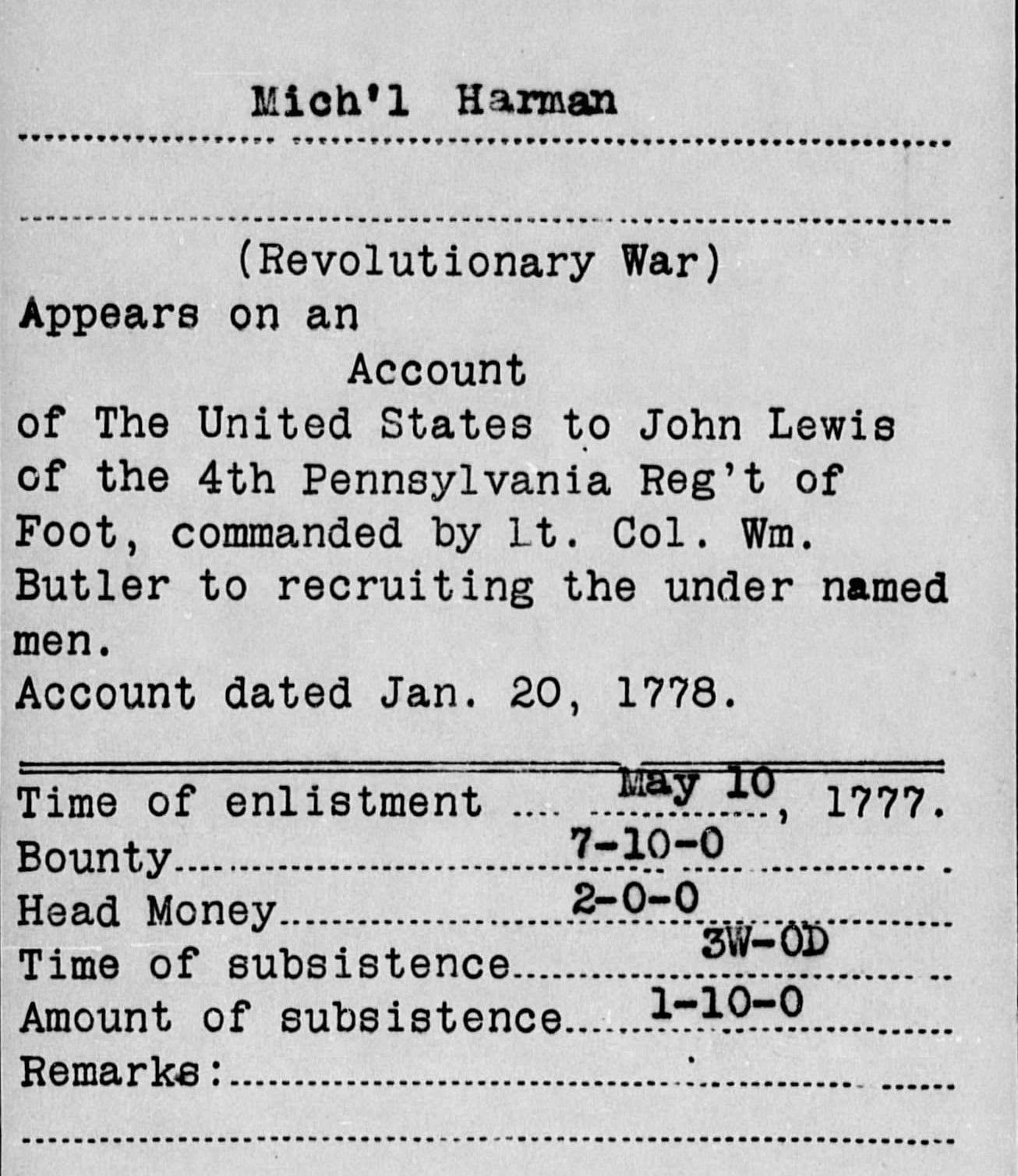

Going to Fold3.com, Horn explains that it is the online place for American military records (it's owned by Ancestry, of course, which he doesn't mention, but it is nice to see the show use a different Web site). He has Harmon enter Michael's name as "Harman" and says she should do so because that's how the name appeared on the records they've looked at (conveniently sidestepping the fact that the search on Fold3 is not very flexible; I still wonder why Ancestry doesn't port its more robust search pages over). Among the results is Michael's Revolutionary War service record. He served under John Lewis in the 4th Pennsylvania Regiment of Foot, an infantry unit. The account date on the card is January 20, 1778. Harmon is very proud that he fought on the American side. Michael enlisted on May 10, 1777 for three years, which was standard (plus he got a bounty!). Harmon notes that he was only 23 years old. Horn has to point out that 1877 was before the end of Michael's indenture period and says that Houts would have received compensation because of that. This causes Harmon to wonder if there was a draft or if Michael volunteered. Horn says it was the latter and that she should think about the risks Michael subjected himself to by being a soldier.

When Harmon asks what happened to Michael after that, Horn says that he sent the documents to his colleague Scott Stephenson, an expert on the Revolutionary War, and that Stephenson "might be able" to tell her more about her ancestor. (Wow, that's pretty impressive! Harmon hasn't even left yet, and Horn has already sent the documents on to someone else. Oh, wait, you mean this was all found ahead of time? Like it's scripted or something?) Harmon effusively begins to thank Horn, then gives him a big hug. She seems very genuine in her enthusiasm (unlike Kelly Clarkson).

In the outro to this segment, Harmon talks about how impressed she is with Michael and all the risks he took, beginning with coming here at only 18 years old. She apparently has a soft spot for troops and really appreciates that Michael volunteered to serve his new country. She also mentions that he went in wholeheartedly, but that's just her embroidering on the story, because we have no idea about that. For all we know, he could have hated his work as a tanner and thought it would be an improvement to be a soldier.

Still in Philadelphia, Harmon now goes to the Free Library to speak with R. Scott Stephenson, Ph.D., director of collections and interpretation (I am so sorry they are using that word that way) at the Museum of the American Revolution. (He helped Valerie Bertinelli with Quaker research.) He says they can reconstruct a lot by using documents. He hands Harmon a (copy of) a voucher dated May 7, 1778 that says "camp near Valley Forge." Michael received $6; this was essentially a pay stub for his work in the army. Stephenson explained that pay in the Continental Army was intermittent and that this was actually back pay. Harmon looks on the voucher where it appears that Michael signed for his payment. Stephenson points out that it actually shows an X and says "his mark", indicating Michael was illiterate.

|

| George Washington and the Continental Army, 1775 |

Stephenson and Harmon drive to Valley Forge National Historical Park. Stephenson explains that the cabins in the park are reconstructions of those that the soldiers, including Michael, used for shelter during their winter encampment. Each "hut" would have housed twelve men. Harmon says, "It's amazing," and I realized she had been saying that several times during the episode, to the point it had become meaningless (but I restrained myself from watching again to count the number of times). When Stephenson and Harmon go into one of the cabins, Harmon discovers that it's pretty cold inside; Stephenson tells her that the buildings were not windtight or sealed from the rain because the men had to make do with minimal tools and no nails to put them together. So while the British were in reasonably comfortable brick buildings in Philadelphia, 2,000 of these cabins housed the Continental Army at Valley Forge. During the winter of 1777–1778, they suffered through shortages of food, clothing, and other supplies, because the Continental Congress was in chaos and couldn't help them. Men caught pneumonia, typhoid, and other diseases, and about 2,500 men died there. But Michael survived, and Harmon is elated to think that she could be walking on the same ground where he had stepped.

Stephenson talks about how these men were fighting for a country with power resting in the people, not a king, which was a radical idea at the time. When Harmon asks whether Michael would have understood the historical significance of what he was taking part in, Stephenson tells her that Washington often told the men that "the fate of millions unborn" depended on what they were doing. Unless Michael still hadn't learned any English, he probably had some idea.

And what happened to Michael after Valley Forge? Stephenson says that most records are in the Pennsylvania State Archives in Harrisburg, and there should be more documents about Michael.

As she leaves Valley Forge, Harmon says how impressed she is with Michael and the strength he had in his heart (um, and where did she learn about that?). He persevered through horrible conditions and was a remarkable man. (Well, he did persevere, I'll give her that.) Obviously, her resilience must have come from him (and now we're back to that theme).

Next up is a visit to Harrisburg and the Pennsylvania State Archives, of course. As Harmon approaches the entrance, she is greeted by Major Sean Sculley, listed as an assistant professor of history at West Point (and boy, does he have a bunch of ribbons on his uniform!). Information about Michael had been sent to Major Sculley, and as expected he had found more to share with Harmon. First is a letter to George Washington from January 2, 1781, letting him know that the 4th Pennsylvania, the regiment Michael was in, had committed mutiny. The unit's captain had been mortally wounded. This sends Harmon into a tizzy — how could Michael do this?!

Major Sculley explains that the sergeants, corporals, and privates in the regiment had mutinied against General Anthony Wayne (apparently known by the nickname of "Mad Anthony"). The men then planned to march to Philadelphia to ask (ok, maybe demand) that Congress give them what they believed they were owed. Michael and the other men had served for up to three years, or more, with hardly any food and little pay. As far as they were concerned, Congress had committed a breach of contract. Men whose enlistment periods had expired were not allowed to leave.

Harmon starts to get all worked up. She goes on about how sad the situation was, that the men couldn't get food or clothes, and really gets a head of steam up. Major Sculley interrupts her to point out that now she's beginning to understand how the men felt at the time. Harmon responds that they had been honorable men (which she really doesn't know; I'm sure not all of them were), and the mutiny was going to be connected to all of their names. Major Sculley points out that it was actually worse than that — mutiny was a capital offense, so they were risking hanging or a firing squad.

Major Sculley adds that Wayne was not really worried about the men going to Philadelphia, but rather that they would head to New York to join up with the British. He shows her another letter, this one from the British to the Pennsylvania Line. The British had offered to provide the men food, clothes, and the back pay that they were owed. All the men had to do was turn their backs on the upstart rebels and return to the British side. Under the circumstances at the time, this was a hard offer to pass up — but they did. When two British spies arrived at the camp with the letter, sergeants involved with the mutiny arrested them and took them to General Wayne. Hey, there's some hope after all! Wayne was able to negotiate with the 76th and 77th (but where does the 4th fit into that?): Men could be discharged and then re-enlist with a new bounty, or simply be discharged and head home.

So which did Michael choose? Major Sculley has a book from the Pennsylvania archives. I didn't see the title, but it has a list of NCO's. Michael's period of service is given as May 5, 1777–1781, so he opted out. Harmon figures out that when he was discharged, he was about 27 years old. And where did he go after that? Major Sculley says that Michael's son Peter was in Mercer County, Kentucky (though I didn't get how he determined that), so he had looked at tax lists for Mercer County. Michael appears on the 1795 list with 130 acres of land, so he actually got land, nominally the reason that he might have left Germany. Harmon comments that Michael was about 41 at the time of the tax list.

Harmon asks Major Sculley if he can tell her anything else. He says they have reached the end of his expertise (Kentucky tax lists actually fall into his field of research?), so if she wants to learn more, she's going to have to go to Kentucky. (Ok, that was expected.)

As Harmon leaves, she admits that her heart had sunk when she heard about the mutiny, but she understands why the men were driven to do it. But Michael had a strong will and strong convictions (again, where did she learn that? did I miss that scene?), and he had been denied what had been promised to him. Then she brings it back to herself (really, is it always about her?): Why does she have such a need for justice? Where could it have come from? Now she knows that she got it from Michael! (Sure, uh-huh.) She gets over herself for a moment and wonders what she will learn about Michael's life in Kentucky. She asks whether he was married — probably, because we've already heard that he had a son — and how many children he might have had (still looking for that big family).

At the Harrodsburg Historical Society, in Harrodsburg, Kentucky (yes, in Mercer County), local historian Amalie Preston meets with Harmon in a curiously empty-looking room. After some disingenuous introductory conversation, Harmon asks if Michael might have left a will. (Of course he did.) Preston has her look at an index, which indicates that a will for Michael Harmon is in Book 3, page 279. After going to page 279 in that book (conveniently on the table), we see the will for M. Harmon, "signed" on July 21, 1807. As with his pay voucher from 1778, there is an "X" and the notation of "his mark." Forty years later, Michael is still illiterate, but he's managed to accomplish a lot. We only get a couple of quick camera shots of the recorded copy of the will, but family members mentioned in bequests are Michael's wife, Peggy (£70), and his children Peter (we heard about him earlier; he's Angie Harmon's ancestor), Michael, Jacob, Peggy, Barbara, Kitty (also £70), and John. Harmon is a little concerned at the bequest to Peter, which says "any of my plantations", and hopes that doesn't mean Michael owned slaves. Preston explains that "plantation" can also be used to mean a big farm, and no, Michael did not own slaves. And now Harmon finally has the big family she has been dreaming about, even if it's from two hundred years ago: "This is where I get my need for a large family." (Seriously?)

Preston tells Harmon she has one more treat coming: She can go to the site where Michael lived. Preston has contacted the present owner and asked for permission for Harmon to visit, and the owner said yes. "Is that something you would like to do?" Of course she would! I actually did like what Harmon said next: "I would love to take my daughters." Now that's a way to try to get the younger generation interested in genealogy and history.

Leaving Harrodsburg, Harmon talks about Michael's bravery and courage (which she couldn't possibly know about, unless one of those researchers showed her some kind of commendation that we didn't get to see on air, but she's bound and determined to make Michael bigger than life) and what an exceptional man he was. She is excited and nervous to see the land he had owned, and is happy that the girls are coming.

As Harmon drives toward the farm with her daughters in the car, she's enthusiastic, and she asks the girls if they're excited. One of them pipes up, "Are we there yet?" As they're pulling up in the car, Harmon admonishes, "Remember your manners, please." (Some things never change, not even for celebrities.)

They are met by a pleasant-looking man, who introduces himself as Michael Harmon (the name was passed down!) and says they are fifth cousins once removed. Harmon introduces her daughters, who have very modern names for girls: Finley, Avery, and Emery (please forgive any misspellings on my part). This Michael says that the land is still owned by Harmons 220 years later, which even I think is great. He tells Harmon that they can see the whole farm from a higher spot and drives the car up there. He points out that the distant treeline is the boundary to the property; all the land, cows, and everything else to that point is the family farm. The girls start running around and playing, and Harmon gets philosophical.

All the fighting, suffering, and hardships Michael (the ancestor) went through were for this. He had a beautiful life and was able to pass that down to herself and the generations to come after her. Being here with her girls has made the journey complete, and now she feels whole. This has given her a new light for the rest of her life and will affect everything she will do, and she is so thankful she was able to experience all of this.

I was kind of surprised at this emotional outpouring, but learning about her ancestor definitely seems to have affected her. Personally, I think it's more than a bit of a stretch to think she "inherited" all the traits she went on about, but if it makes her happy to think Michael Harmon passed that down to her, who am I to burst her bubble?

Something I was struck by was how Harmon kept track throughout the episode of about how old Michael was at each event in his life she learned about. I don't understand why it was so significant to her, but she was pretty consistent about it. The only time I didn't hear her figure out his age was when she was looking at the will, which seemed counterintuitive. After all, that was around the time he died, an age more people tend to be interested in.

Something else I noticed was that even though Harmon did find her big family, she didn't get the other tidbits we heard about in the beginning: She didn't find any paintings or other pictures of her ancestors (no photos, as Michael died about 1807, before the age of photography), and even though she was "convinced" her father had Irish or Scottish ancestry, we didn't hear about that again. Usually when the celeb talks about something like that, we see it later on. Could the producers be deliberately giving us false leads so we don't automatically know what to expect in an episode?

I saw that same Ancestry.com advertisement where the actress says she found her grandfather's World War I draft card but what's shown is a card for World War II. I'm beginning to consider the possibility that the reason it isn't being changed is the same as why we don't see quality control in the databases on the Web site: It isn't costing them any business to air such an egregious mistake, so why spend money to fix it?

Now that we're in the third season of WDYTYA on TLC, I am beginning to see a little bit of a "formula" for the celebrities chosen. First is the apparent marketing to a younger demographic, with actors generally more relevant to that group. While on NBC each season had at least one black and one Jewish celebrity, on TLC each season has had at least one gay celebrity. We still have somewhat of a nod to having a Jewish celebrity — Chelsea Handler (first season) is half Jewish; Josh Groban's father grew up Jewish but converted for marriage. Previously we have had only white Western European celebrities, but this season has Julie Chen and America Ferrera. It'll be interesting to see what happens going forward.

In a fun little coincidence, the night after this episode aired, Antiques Roadshow had an appraisal of a letter written by George Washington from Valley Forge in 1778. (The link is currently having some problems, but I hope PBS fixes it soon.)

And I actually had finished writing this before tonight's episode with Sean Hayes, but I wasn't able to post it before the episode started!